Emily Murphy, one of Canada’s pioneering feminists, was recently honoured by Justin Trudeau, who left out her dark history.

Joshua Ostroff

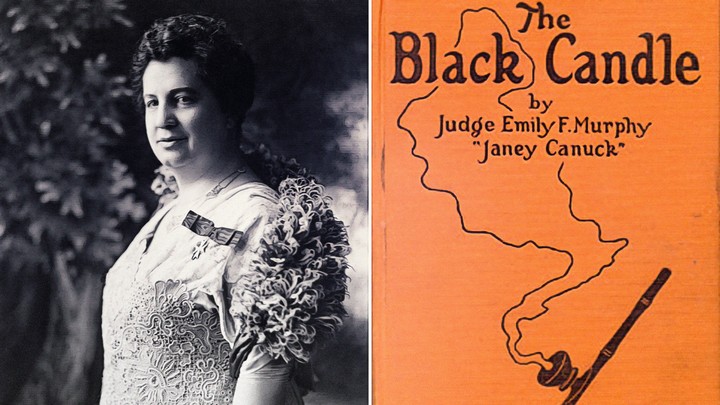

Image sources: Wikipedia Commons

Canada’s yearlong celebration of its history has been consistently sullied by, well, its history, from people pointing out John A. MacDonald’s genocidal tendencies to protests over the statue of Edward Cornwallis, the Halifax founder who placed bounties on Mi’kmaq scalps, including children.

Perhaps the feds were hoping to rectify that by having this year’s Canadian History Week theme be human rights. Which brings us to Canadian historical icon Emily Murphy, leader of the pioneering feminists known as the Famous Five. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau described Murphy and friends just last month as “trailblazers for social justice” who “defined the future of our country.”

This is true. But what JT left out is that Murphy’s influence on Canada was as grotesque as it was great. In fact, Trudeau was elected on the promise of undoing the lesser-known part of her legacy that defined the future of our country’s racist marijuana laws.

Murphy is a perfect example of how history isn’t just written by the victors—it’s also edited by their descendants. Take her 1992 “Heritage Minute,” one of the patriotism-stoking government ads that have attained retro-90s cult status, and which federally-funded Historica Canada proudly reposted on YouTube just last year.

Oscar-nominated actress Kate Nelligan’s in-character monologue explains how Murphy, the first female judge in the British Empire, led a decade-long struggle that eventually saw Canadian women legally recognized as persons in 1929. (Most women, that is. Indigenous women are still waiting in 2017 for the passage of Bill S-3, a court-ordered Indian Act amendment ending the “sex-based inequities” it has enshrined in law since 1876.)

For winning the “Persons Case,” Murphy understandably received a place in history, a plaque in the senate, a brief stint on the $50 bill, an Edmonton park and statues on Parliament Hill and across the country. If you read the (sadly Vin Diesel-free) Famou5.ca website, you’ll learn a lot about Murphy—just not about how she spread racist drug panic across Canada and is widely considered the mother of marijuana prohibition.

That

“Heritage Minute” ad did actually mention Murphy’s work as the “author

of the Janey Canuck books [and] pioneer in the war against narcotics,”

it just left out the context. (It also left out her vocal support for eugenics

which helped pass Alberta's Sexual Sterilization Act in 1928. Nearly

5,000 women with mental disabilities were sterilized before it was

repealed in 1972.) A TV biography of Murphy made in 1999, also available on YouTube,

admits her findings inspired drug legislation into the 1960s but

dismisses modern criticism: “It sounds racist now—and it was racist, I

guess—but that's what she found as a result of her research."

Murphy’s research was initially published in a series of articles for Maclean’s under the pen name Janey Canuck which, according to the book Crime and Deviance in Canada: Historical Perspectives, were commissioned "for the express purpose of arousing public demands for stricter drug legislation." In 2010, the magazine even published a mea culpa headlined “The Secret Shame of Maclean’s.”

Those articles became the basis for her 1922 best-selling book The Black Candle, alongside original chapters like “Marahuana—A New Menace.” Her conspiracy-theory thesis was that “aliens of colour” had formed a drug syndicate called The Ring to “bring about the downfall of the white race.”

Her lurid prose warned smoking opium would lead to “the amazing phenomenon of an educated gentlewoman, reared in refined atmosphere, consorting with the lowest classes of yellow and black men” and that an addicted woman “doesn't work for anyone but the negro who buys her for the price of opium where with to ‘hit the pipe.’” She also described dealers boasting about “how the yellow race would rule the world” and that “some of the Negroes coming into Canada—and they are no fiddle-faddle fellows either—have similar ideas: and one of their greatest writers has boasted how ultimately they will control the white men.”

Anti-Chinese

sentiment in Vancouver had already led to non-medical use of opium

being outlawed in 1908, with cocaine and morphine added in 1911. So

aside from salaciously vilifying POC even further and spreading hate

across the country, what her best-seller added to the national

conversation was its warning about cannabis.

Cannabis was almost unknown in Canada at the time, making it easy for Murphy to claim it was poison that would end in “untimely death.” That is, after turning its users into “raving maniacs [who] are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility.” For publishing this “research,” she nominated herself for a Nobel Prize.

In her book Jailed for Possession, University of Guelph professor Catherine Carstairs has claimed Murphy’s influence was “overstated both by herself and subsequent drug scholars.” But she also acknowledges that “Murphy’s articles did mark a turning point, and her book...brought the Vancouver drug panic to a larger Canadian audience.” Public opinion, of course, is a propellant for such legislation and cannabis wound up added to Canada’s anti-drug law a year after Black Candle’s publication. Canada was the first western country to do so, a full 14 years before the US.

Why does all this matter in 2017? Because it’s important to acknowledge that pot prohibition was born and raised in racism so that we don’t let this problematic past dictate our future.

This week Health Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor announced that the feds want to know if Canadians support letting people with pot charges into the legal industry. "We have over 500,000 Canadians with minor drug offences on their criminal records,” she said at a November 21 press conference. “We're just asking the question: should these people with a small amount of personal possession, should they be excluded from the market or should we consider them?"

To dig deeper into this question than the minister [publicly] did, a recent Toronto Star report revealed black people with no criminal history are three times more likely than white people to be arrested for possession. Even pot czar (and former police chief) MP Bill Blair admitted in 2016 that “one of the great injustices in this country is the disparity and the disproportionality of the enforcement of these laws and the impact it has on minority communities, Aboriginal communities and those in our most vulnerable neighbourhoods.”

So if people of colour are kept out of the post-prohibition industry because they have criminal records due to race-based enforcement, then that disparity and disproportionality will continue—and Emily Murphy will keep winning the wrong case.

Perhaps the feds were hoping to rectify that by having this year’s Canadian History Week theme be human rights. Which brings us to Canadian historical icon Emily Murphy, leader of the pioneering feminists known as the Famous Five. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau described Murphy and friends just last month as “trailblazers for social justice” who “defined the future of our country.”

This is true. But what JT left out is that Murphy’s influence on Canada was as grotesque as it was great. In fact, Trudeau was elected on the promise of undoing the lesser-known part of her legacy that defined the future of our country’s racist marijuana laws.

Murphy is a perfect example of how history isn’t just written by the victors—it’s also edited by their descendants. Take her 1992 “Heritage Minute,” one of the patriotism-stoking government ads that have attained retro-90s cult status, and which federally-funded Historica Canada proudly reposted on YouTube just last year.

Oscar-nominated actress Kate Nelligan’s in-character monologue explains how Murphy, the first female judge in the British Empire, led a decade-long struggle that eventually saw Canadian women legally recognized as persons in 1929. (Most women, that is. Indigenous women are still waiting in 2017 for the passage of Bill S-3, a court-ordered Indian Act amendment ending the “sex-based inequities” it has enshrined in law since 1876.)

For winning the “Persons Case,” Murphy understandably received a place in history, a plaque in the senate, a brief stint on the $50 bill, an Edmonton park and statues on Parliament Hill and across the country. If you read the (sadly Vin Diesel-free) Famou5.ca website, you’ll learn a lot about Murphy—just not about how she spread racist drug panic across Canada and is widely considered the mother of marijuana prohibition.

Murphy’s research was initially published in a series of articles for Maclean’s under the pen name Janey Canuck which, according to the book Crime and Deviance in Canada: Historical Perspectives, were commissioned "for the express purpose of arousing public demands for stricter drug legislation." In 2010, the magazine even published a mea culpa headlined “The Secret Shame of Maclean’s.”

Those articles became the basis for her 1922 best-selling book The Black Candle, alongside original chapters like “Marahuana—A New Menace.” Her conspiracy-theory thesis was that “aliens of colour” had formed a drug syndicate called The Ring to “bring about the downfall of the white race.”

Her lurid prose warned smoking opium would lead to “the amazing phenomenon of an educated gentlewoman, reared in refined atmosphere, consorting with the lowest classes of yellow and black men” and that an addicted woman “doesn't work for anyone but the negro who buys her for the price of opium where with to ‘hit the pipe.’” She also described dealers boasting about “how the yellow race would rule the world” and that “some of the Negroes coming into Canada—and they are no fiddle-faddle fellows either—have similar ideas: and one of their greatest writers has boasted how ultimately they will control the white men.”

Cannabis was almost unknown in Canada at the time, making it easy for Murphy to claim it was poison that would end in “untimely death.” That is, after turning its users into “raving maniacs [who] are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility.” For publishing this “research,” she nominated herself for a Nobel Prize.

In her book Jailed for Possession, University of Guelph professor Catherine Carstairs has claimed Murphy’s influence was “overstated both by herself and subsequent drug scholars.” But she also acknowledges that “Murphy’s articles did mark a turning point, and her book...brought the Vancouver drug panic to a larger Canadian audience.” Public opinion, of course, is a propellant for such legislation and cannabis wound up added to Canada’s anti-drug law a year after Black Candle’s publication. Canada was the first western country to do so, a full 14 years before the US.

Why does all this matter in 2017? Because it’s important to acknowledge that pot prohibition was born and raised in racism so that we don’t let this problematic past dictate our future.

This week Health Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor announced that the feds want to know if Canadians support letting people with pot charges into the legal industry. "We have over 500,000 Canadians with minor drug offences on their criminal records,” she said at a November 21 press conference. “We're just asking the question: should these people with a small amount of personal possession, should they be excluded from the market or should we consider them?"

To dig deeper into this question than the minister [publicly] did, a recent Toronto Star report revealed black people with no criminal history are three times more likely than white people to be arrested for possession. Even pot czar (and former police chief) MP Bill Blair admitted in 2016 that “one of the great injustices in this country is the disparity and the disproportionality of the enforcement of these laws and the impact it has on minority communities, Aboriginal communities and those in our most vulnerable neighbourhoods.”

So if people of colour are kept out of the post-prohibition industry because they have criminal records due to race-based enforcement, then that disparity and disproportionality will continue—and Emily Murphy will keep winning the wrong case.

No comments:

Post a Comment