By Lee V. Gaines

E

ddy, a burly 65-year-old professional musician, walked into a free legal

clinic in Los Angeles County one July morning hoping to clear his

record. More than three decades ago, he served two years probation for

attempting to sell a few gram bags of marijuana, a felony that put the

immigrant, a legal U.S. resident with a green card, at greater risk of

deportation.

Thanks to Proposition 64, the California ballot initiative that

legalized the recreational use of marijuana last November, Eddy has a

chance for a clean slate. Under one provision of the law, many people

with pot-related convictions can apply to have them reduced to lesser

offenses or expunged, the legal term for having a case dismissed.

Eddy was one of several dozen people, mostly Latinos and

African-Americans, who attended the legal clinic at Chuco’s Justice

Center, a graffiti-covered community center in the small city of

Inglewood, which borders Los Angeles International Airport. Staffed by

volunteers from the national drug reform nonprofit, Drug Policy

Alliance, and lawyers from the Los Angeles County public defender’s

office, the clinic was one in an ongoing series of events held in recent

months to help people get convictions reduced or dismissed.

A little more than a year after the passage of Prop. 64, at least

2,660 petitions have been filed to reduce sentences for people convicted

of pot-related offenses. At least another 1,500 petitions have been

filed to reclassify old felony marijuana convictions as misdemeanors or

to dismiss them altogether, depending on the offense, according to the

Judicial Council, the policy-making arm of the state courts.

California’s Prop. 64, the

California ballot initiative that legalized the recreational use of

marijuana last November, built on Prop. 47, which allowed for the

reduction of some nonviolent felonies, including theft and some drug

charges, to misdemeanors. Joyce Kim for The Marshall Project

Those figures include self-reported data from a majority of the

state’s 58 counties through September, and may be under-reported.

According to several public defenders around the state, the Judicial

Council’s figures don’t reflect all of the petitions their offices

reported filing on behalf of their clients. The Council also doesn’t

record the outcome of the requests.

Although the numbers of Prop. 64 applicants so far represent only a

portion of the people who have been convicted of pot felonies in recent

decades, advocates remain hopeful that as the public learns about the

law, more will come forward to have offenses reduced or cleared.

At Chuco’s Justice Center that morning, Eddy was one of about 40

people who received legal assistance, including consultations with

paralegals and attorneys, court records checks, and live scan

fingerprinting to obtain criminal records from other counties.

Eddy’s conviction was ultimately vacated. Now that his rap sheet is

clean, he says he’ll pursue citizenship. “I’m lucky to live in

California,” said Eddy, whose father brought him to the U.S. from

Central America when he was 9.

He’s right.

Twenty-nine states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam

have legalized medical marijuana, and eight states plus D.C. have

sanctioned recreational use. But fewer states have made it possible to

clear past marijuana offenses. In the last three years, at least nine

states have passed laws addressing expungement of certain marijuana

convictions, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

But no state goes as far as California.

For thousands of Americans, marijuana convictions still bring

life-altering consequences, making it difficult to, among other things,

find and keep a job, get a professional license or obtain a student

loan.

Communities of color have been hit especially hard by the

decades-long war on drugs. Studies show a stark racial imbalance in drug

enforcement; a 2013 American Civil Liberties Union report concluded

that African-Americans were nearly four times more likely to be arrested

for marijuana possession than whites, although use of the drug was

roughly equal among the races.

Across California, attorneys and drug reform advocates say

implementation of Prop. 64 hasn’t been perfect; more resources are

needed to process petitions and conduct outreach to people who may be

eligible to clear their records and just don’t know it. But overall,

they believe the law is an effective tool to undo the collateral damage

of felony pot convictions, and they hope it will serve as a model for

the rest of the country.

Prop. 64 “gives people the opportunity to recreate themselves and

become people instead of statistics,” said Nick Stewart-Oaten, a deputy

public defender for Los Angeles County.

C

alifornia’s Prop. 64, also known as The Adult Use of Marijuana Act, made

it legal for adults to possess and grow small amounts of pot at home,

brought some pot-related felonies down to misdemeanors and some

misdemeanors down to infractions, and reduced or dismissed prior

convictions.

The initiative built on a 2014 law known as Prop. 47, which allowed

for the reduction of some nonviolent felonies, including theft and some

drug charges, to misdemeanors.

To apply for a reduction under Prop. 64, a petitioner files in the

court in which they were convicted, usually with the help of a public

defender or a private lawyer. The district attorney’s office reviews

each petition, which is then approved or rejected by a judge. The

process can take from days to weeks depending on the location.

In some counties, officials didn’t wait for people to come forward to

apply for relief under the law; they started the process for them. Soon

after Prop. 64 passed, the L.A. County public defender’s office

identified people in prison or on parole for marijuana-related offenses

and filed petitions for resentencing on their behalf, according to

Stewart-Oaten, who said his office has filed 564 such petitions so far.

Similarly, San Diego’s Deputy District Attorney Rachel Solov said her

office used their case management system to identify hundreds of

eligible people serving a sentence or who were on probation or

supervision and then provided the data to the local public defender’s

office so that attorneys there could begin filing petitions for those

individuals.

“Our primary concern was getting people out of custody who were in custody and shouldn’t be,” Solov said.

Contra Costa County took a similar approach, according to Deputy

Public Defender Ellen McDonnell. Her office identified roughly 2,500

people who appeared to be eligible to have convictions reclassified or

dismissed on cases dating back 25 years, she said. So far, the office

has filed about 80 petitions, mostly for reclassification of old

convictions. The office is now engaged in “aggressive community

outreach” in the hopes of finding more people who could benefit from the

new law, she said.

Identifying everyone eligible for relief under Prop. 64 has been one of the biggest challenges so far, Stewart-Oaten said.

Original analysis and perspectives from across the spectrum on criminal justice

The public defender’s office doesn’t have the capacity to comb

through decades of case files to figure out who may qualify, find their

contact information, and persuade them to come into their office to

start the paperwork process, he said. The office works with partners

like Drug Policy Alliance to help reach people at free legal clinics

like the one at Chuco’s Justice Center.

“We recognize it’s not enough, but we are limited in what we can do.

We don’t have an advertising budget. A lot of times we are acting on

word of mouth,” Stewart-Oaten said.

Alameda County Deputy Public Defender Sue Ra said her office hasn’t

received any additional funding for post-conviction relief services,

which could help attorneys reach more people and process their petitions

faster.

“Somebody needs to do this work, and the public defenders are on the

ground actually doing it,” Ra said. “It would be nice to get the support

to allow us the resources to complete work quickly so that our clients

don’t miss out on employment and other opportunities.”

A

s thousands of Californians line up to have their records cleared,

Americans with pot convictions in many other states have no such

opportunity. Will more states follow California’s lead?

Robert Mikos, a professor at Vanderbilt Law School, isn’t so optimistic.

Many politicians have come around on marijuana legalization, aided by

the lure of potential tax revenue and new jobs, Mikos said. Nearly

two-thirds of Americans support

legalization in a recent poll. But many people appear reluctant to

support post-conviction relief for marijuana offenders.

“It’s a tougher

sell to say, you know what, these people flouted these rules ... and we

ought to wipe those records clean,” said Mikos, an expert on marijuana

law.

Even in Washington state, where recreational pot has been legal since

2012, lawmakers have not passed a law that specifically lets people

clear old pot offenses. (Those convicted of certain nonviolent crimes,

including marijuana-related ones, can already apply to vacate their

records but must wait years after completing their sentences; five for

some low-level felonies and three for misdemeanors.)

There are exceptions. Although no state has passed a law as sweeping

as California’s, several recently have enacted measures that allow pot

offenses to be reduced or expunged. In the past year, for example,

Colorado began allowing old convictions for misdemeanor marijuana

possession or use to be sealed so long as the act wouldn’t be considered

illegal today. In Maryland, a new law lets people convicted of

marijuana possession apply for expungement four years after the

completion of their sentence; the previous wait time was a decade.

A Missouri law set to take effect next year reduces the wait time to

expunge nonviolent felonies, including marijuana-related convictions,

from 20 to seven years and from 10 to three years for misdemeanors. And

in Massachusetts, where recreational pot sales will begin in mid-2018,

marijuana possession convictions can now be sealed, which removes them

from public view but doesn’t dismiss them. (Lawmakers tossed out a

proposed measure to expunge marijuana offenses.)

On the federal level, Mikos points to a bill filed in August by New

Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, a Democrat, that could be a blueprint for

post-conviction relief on a national scale. The proposal would

decriminalize marijuana and expunge federal convictions for possession

of the drug.

Booker’s bill would allow the federal government to withhold cash

from states with arrest and conviction rates that disproportionately

impact the poor and minorities. That approach could be used to pressure

states to provide resentencing, reclassification and expungement for

marijuana offenses, Mikos said.

However, given Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ pledge to crack down

on drug offenders, and his distaste for marijuana legalization in

general, any federal measure to decriminalize marijuana may be a pipe

dream for reform advocates, Mikos added.

On the state level, even where marijuana use is legal, politicians

may never pass laws similar to Prop 64. “Part of that is just that we

live in a federal system, and that’s the nature of the game,” Mikos

said. “Different states are going to do things differently.”

Community organizers who rallied public support for Prop. 64 last

year in California have some advice for people in other states: Do the

work yourself.

Ingrid Archie, a legal clinic coordinator with A New Way of Life, a

Los Angeles nonprofit that supports formerly incarcerated women, didn’t

want to rely on mostly white, wealthy California legislators to pass

meaningful criminal justice reforms. That’s why she campaigned for Prop.

64 in the communities impacted the most by marijuana prohibition —

people of color and low-income neighborhoods.

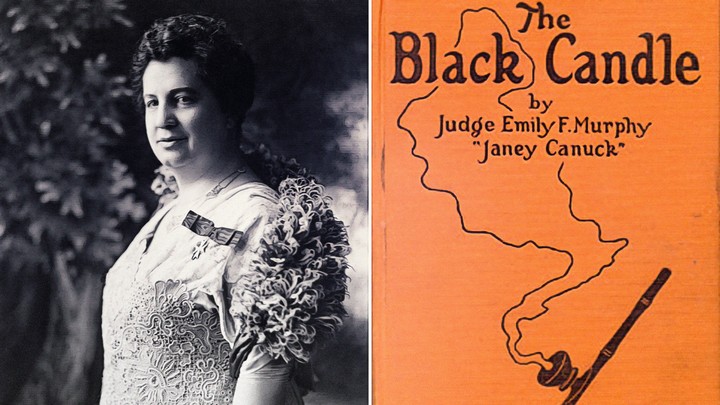

Ingrid Archie, at home with

her children, was convicted of possession with intent to sell marijuana

in 2004. She applied to have her record expunged under Prop. 64. Joyce Kim for The Marshall Project

The African-American mother and grandmother had a personal investment

in the issue: Convicted of possession with intent to sell marijuana in

2004, she lost a job, a home and was re-incarcerated after being

convicted of child endangerment after she left one of her children in

her car while she went into a store to purchase diapers and milk. “It

was a trickle of consequence after consequence after consequence all

stemming from a marijuana charge,” she said.

Archie contends that grassroots organizing persuaded low-income

minorities who may not have supported the idea of legal weed to

ultimately back the measure. While Prop. 64 passed with 57 percent of

the overall vote, 64 percent of African-Americans backed the ballot initiative compared to 58 percent of white voters.

Archie, who lined up to be one of the first people to apply for

expungement under Prop. 64 last year — she started the paperwork a

little after midnight on election night last year — hopes organizers and

reform advocates in other states follow California’s lead.

If they don’t act, and politicians don’t act, Archie said, millions

will continue to suffer the consequences of the war on drugs. Felony

records, she said, “ruin people’s lives.”