David knocked on the table three times.

“My name is David, and I’m a marijuana addict,” he said.

“Hey, David,” the other two attendees replied in unison. A fan in the hospital basement room whirred loudly in the background.

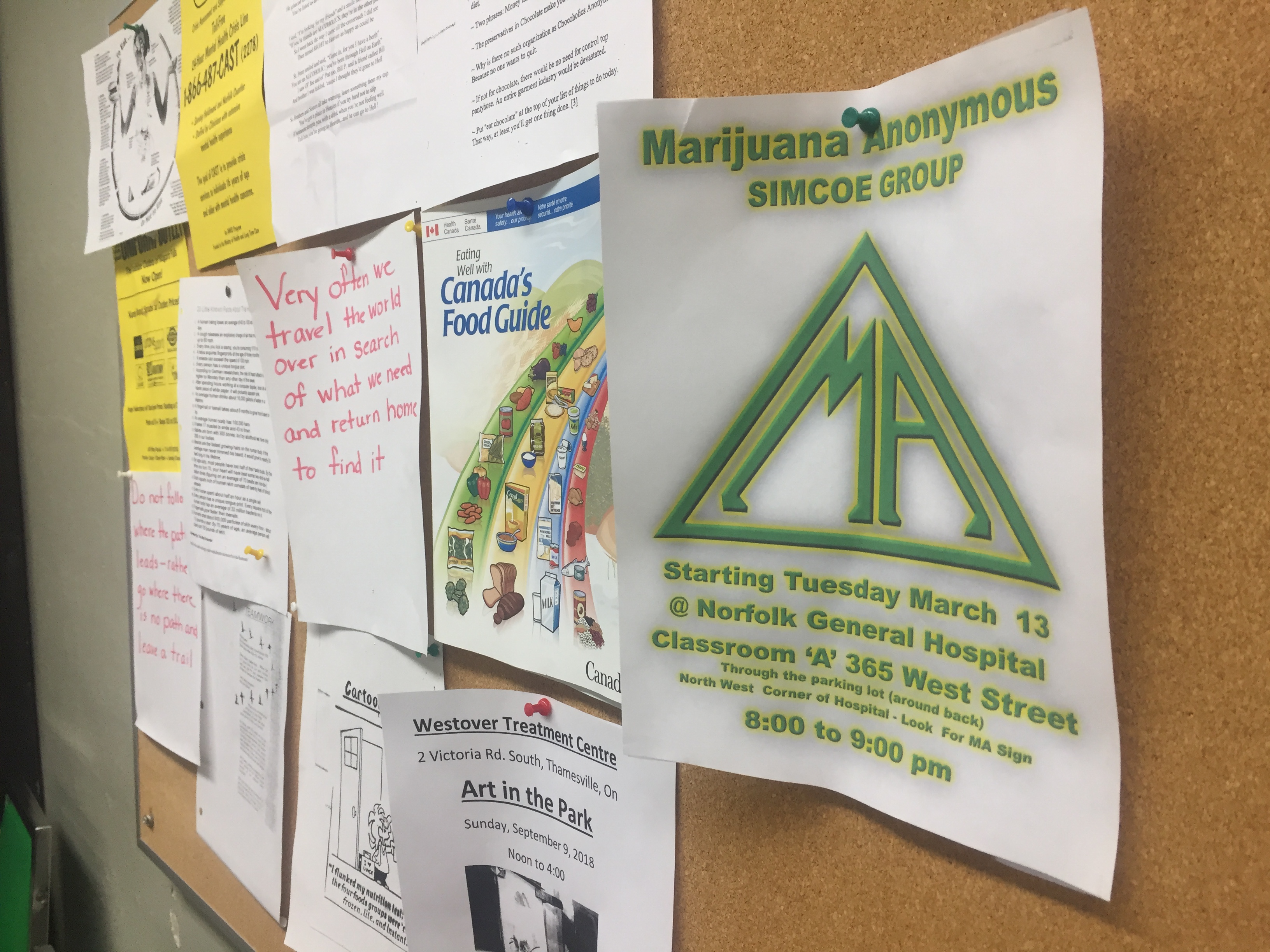

So began the meeting of Marijuana Anonymous in Simcoe, Ontario, about two hours outside of Toronto. The first meeting started here in the city of 14,000 this past March, one of only a dozen or so MA meetings across the rest of Canada. The turnout for this early July meeting was especially small, at just three. Usually there are at least five people.

By comparison, there are hundreds of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings across Canada. But for these self-identified marijuana addicts, those recovery groups aren’t sufficient.

They don’t necessarily fit in with the alcoholics, and say they sometimes get dismissed by Narcotics Anonymous members who see cannabis as child’s play compared to coke or heroin. It’s a unique substance in the world of addiction as it continues to gain wide acceptance as a medication, and becomes more normalized through legalization.

“Marijuana Anonymous is a fellowship of people who share our experience, strength, and hope with each other, that we may solve our common problem and help others to recover from marijuana addiction,” David recited from a script. He’s not using his full name, in accordance with the group’s chief rule that everyone abide by total anonymity.

“The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop using marijuana,” continued David, who said he had never heard about the group before finding it online. The group also offers online support chat rooms and phone meetings. He said he had tried other recovery programs, as someone who also struggles with alcohol, but those didn’t help him address his cannabis use. Many members say they struggle with both alcohol and cannabis addiction.

“I knew I had a problem,” David continued. “My life had become totally unmanageable. I had become totally isolated … smoked a lot of joints.” He added he eventually lost so much weight that he could barely move.

Like AA, Marijuana Anonymous meetings are structured around consistent routines based on the group’s readings. The program itself is adapted from the 12 steps of AA, essentially swapping out the word “alcohol” for “marijuana” and its variations.

The first step of MA, for example, states “we admitted we were powerless over marijuana, that our lives had become unmanageable.” Step nine involves making “direct amends” with with anyone harmed as a result of the addiction, if possible.

After a few readings by the other members, it was time for the Simcoe group to acknowledge sobriety milestones.

“They’re called Stones for Stoners,” David says as another member named Michael placed a number of rocks of varying shapes onto the table that he’s painted with the group’s logo: the letters M and A pushed together to form a triangle, similar in style to that of AA’s.

“I should probably collect because I’m 21 days away from nine months without weed,” David said, choosing a tiny rock painted with purple.

“Pass it over here,” Michael said, taking the stone and squeezing the black paint to put the year count on it. Michael himself was coming up on this 8th year of sobriety.

“Currently, it’s 2,912 days,” he said, holding up his phone with the Marijuana Anonymous app on the screen. It has a sobriety counter, the readings, and a meeting tracker.

Marijuana Anonymous group poster. (Rachel Browne for VICE News.)

Even though one pillar of the group is to refrain from giving any opinions or engaging in external “controversies,” the topic of cannabis legalization has cropped up among members, especially as American states and countries such as Canada legalize cannabis for recreational use.

And cannabis addiction has come up repeatedly in public debates around changing cannabis laws.

Health experts say that roughly 10 percent of people who use cannabis could become addicted to it — a much smaller percentage than with other drugs or tobacco — and the number people addicted is expected to rise in tandem with an increase in the number of people using the substance.

For David Juurlink, an addictions expert and head of clinical pharmacology and toxicology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, there is no question as to whether cannabis addiction exists.

But because of its far more subtle withdrawal symptoms compared to alcohol or opioids, many people may perceive it as inherently safe. "Unhealthy cannabis use is in the eye of the beholder and some people will choose not to view their own cannabis use as unhealthy," Juurlink said in a phone interview.

If someone is using cannabis in a way that interferes with their obligations at work or at home and is unable or has great difficulty stopping cannabis use, that meets the conventional criteria for addiction, and they could have a problem, Juurlink continued.

“Alcohol withdrawal kills people. Once people drinking 40 ounces of alcohol a day stop, they can go into withdrawal and they can die. Opioid withdrawal is a big deal,” he said. “Someone who is a heavy user of cannabis who stops is not going to die. They are going to have trouble sleeping, they’re going to be irritable, they might have weird dreams, they might have anxiety. And all of these things might get better when they resume their cannabis again.”

Those at the Simcoe meeting said it took them a long time to recognize the impact their cannabis use had on their lives.

Michael described it as a silent addiction. “No one sees you, you’re not out robbing people.

You’re not beating people up, you’re not getting into fights,” he said. “So for the rest of society, you’re not really a problem. You’re just a problem to yourself because you’re not doing anything with your life.”

“It’s like being kicked to death by a bunny.”

One of the reasons people might hold the view that cannabis is safer is because the withdrawal syndrome is kind of non-specific and could easily be attributed to something else, said Juurlink.

While he agrees that cannabis legalization is the right thing to do, he worries that there will be a subset of the population — “a small subset hopefully” — whose use is so heavy that they will check out in terms of their productivity.

And as Canada embarks on a national experiment to fully legalize the substance for recreational purposes, there are pros and cons that come with that. “On balance, the pros of the experiment outweigh the cons,” said Juurlink. “But I think it’s incumbent upon the government to do what it can to minimize the societal harms that can come from access use of cannabis, and cannabis addiction is one of those things.”

Canada might be a bit player in the Marijuana Anonymous universe, but over the next year, it will become an important place as the group prepares to host its 2019 world convention and conference in Toronto and Vancouver. It’s the first time delegates from the group will meet outside of the United States. It also happens to be months after Canada’s legal recreational market officially opens on October 17th, something members say is completely coincidental.

There are currently around 20 so-called Marijuana Anonymous districts around the world, and about as many “independent ones” that do not have official status from the broader group. A district can contain multiple meetings.

Marijuana Anonymous was formed in California in 1989, more than 50 years after Alcoholics Anonymous was founded by two men in Ohio. MA was an amalgamation of three separate recovery groups for people addicted to cannabis. The first conference to figure out the details of combining those disparate groups took place in a “crowded motel room” halfway between San Francisco and LA, according to the group’s own literature on its history.

Within a couple of years, MA became aware of similar groups that had also formed around the world, something they considered serendipitous.

“All of these small groups had started one at a time, almost simultaneously, not even knowing of any other group’s existence,” the group’s bio, authored by MA’s “literature committee,” continues.

"Stones for Stoners" at the Simcoe Marijuana Anonymous group. (Rachel Browne for VICE News.)

While the group has no headquarters or leadership hierarchy, there are rotating volunteers on the Trustees of Marijuana Anonymous World Services based in California.

The public information trustee, who wished to be identified as Josh, told VICE News in a phone call from Los Angeles there has been a 51 percent spike in calls to the main phone line over the last year from people expressing interest in it — there were 419 calls as of mid-July of this year, up from 278 calls at the same time in 2017.

That increase in interest comes as the group launches what it describes as a more “aggressive” social media strategy through targeted ads on platforms like Instagram, Reddit, Snapchat, and Facebook.

“When people are scrolling through and hitting their vape, at least they can see an ad saying ‘is MA right for you?’ With social media, thankfully we can use some targeted demographics to hit some groups that maybe need to hear our message,” Josh said.

Josh guesses that a rough poll would reveal that nine out of 10 people would know what Alcoholics Anonymous is. Maybe two people out of 10 would know about Marijuana Anonymous.

But he’s careful to add that this new outreach is not a form of promotion — something that goes against one of their founding principles that states the group should be about “attraction rather than promotion.”

“We’re not offering free t-shirts if you show up for a meeting or anything like that,” he added. “We just haven’t had a presence in the social media space, and we’re about to.”

As the group ramps up its digital footprint, it also recognizes that legalization will likely have an impact on the group’s attendance numbers, but it’s not something they track.

“As legalization happens and becomes more ingrained in our culture, we probably will see a rise in attendance but at the same time, we’re an anonymous corporation. So nobody is signing in at the door, I don’t have a clicker in my hand as people come into a meeting,” said another MA trustee who wanted to be identified as Lori, who was on the same phone call as Josh. Lori said she joined MA 13 years ago after hearing about it from a psychiatrist. She said she self-medicated with pot for a “myriad of mental disorders.”

“I was miserable and I was lonely, so eventually I ran out of excuses as to why my life was a mess,” Lori explained. “There’s all these conjectures and this thinking that pot’s not addictive, so as an addict I latched onto that. Then I get to MA and I hear the stories and I see the recovery and I say ok, I will give this a shot. And things went much better.”

No comments:

Post a Comment