Why? Because the feds are bogarting the weed, while Israel and Canada are grabbing market share.

Lyle Craker is an unlikely advocate for any

political cause, let alone one as touchy as marijuana law, and that’s

precisely why Rick Doblin sought him out almost two decades ago. Craker,

Doblin likes to say, is the perfect flag bearer for the cause of

medical marijuana production—not remotely controversial and thus the

ideal partner in a long and frustrating effort to loosen the Drug

Enforcement Administration’s chokehold on cannabis research. There are

no counterculture skeletons in Craker’s closet; only dirty boots and

botany books. He’s never smoked pot in his life, nor has he tasted

liquor. “I have Coca-Cola every once in a while,” says the quiet,

white-haired Craker, from a rolling chair in his basement office at the

University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where he’s served as a professor

in the Stockbridge School of Agriculture

since 1967, specializing in medicinal and aromatic plants. He and his

students do things such as subject basil plants to high temperatures to

study the effects of climate change on what plant people call the

constituents, or active elements.

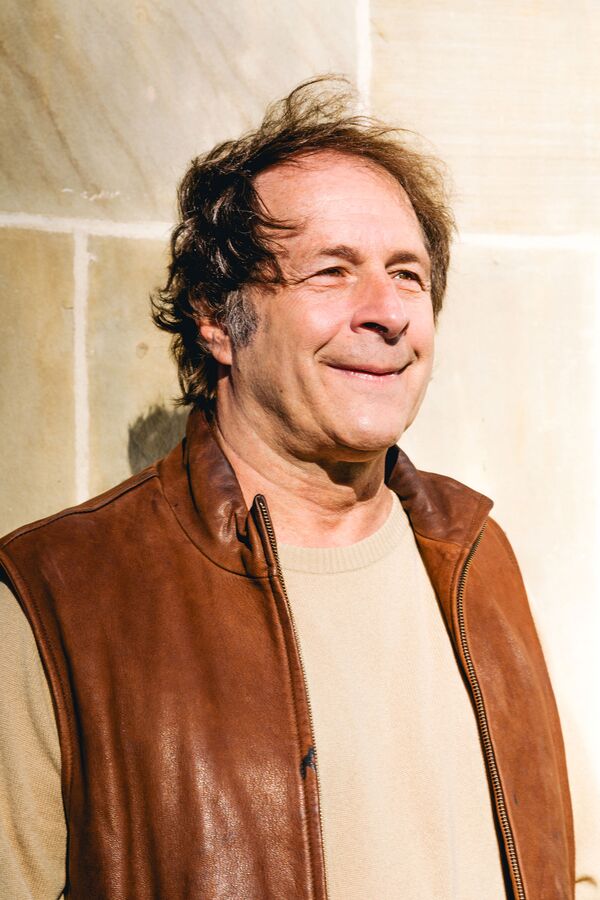

Rick Doblin, relentless advocate.

Photographer: Jonathan Schoonover for Bloomberg Businessweek

The NIDA license, Doblin says, is a “monopoly” on the supply and has starved legitimate research toward understanding cannabinoids, terpenes, and other constituents of marijuana that seem to quell pain, stimulate hunger, and perhaps even fight cancer. Twice in the late 1990s, Doblin provided funding, PR, and lobbying support for physicians who wanted to study marijuana—one sought a treatment for AIDS-related wasting syndrome, the other wanted to see if it helped migraines—and was so frustrated by the experience that he vowed to break the monopoly. That’s what led him to Craker.

In June 2001, Craker filed an application for a license to cultivate “research-grade” marijuana at UMass, with the goal of staging FDA-approved studies. Six months later he was told his application had been lost. He reapplied in 2002 and then, after an additional two years of no action, sued the DEA, backed by MAPS. By this point, both U.S. senators from Massachusetts had publicly supported his application, and a federal court of appeals ordered the DEA to respond, which it finally did, denying the application in 2004.

Then, in August 2016, during the final months of the Obama presidency, the DEA reversed course. It announced that, for the first time in a half-century, it would grant new licenses.

Doblin, who has seemingly endless supplies of optimism and enthusiasm, convinced the professor there was hope—again. So Craker submitted paperwork, again, along with 25 other groups.

The university’s provost co-signed his application, and Senator Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) wrote a letter to the DEA in support of his effort.

He’s still waiting to hear back. “I’m never gonna get the license,” Craker says.

Pessimism isn’t surprising from a man who’s been making a reasonable case for 17 years to no avail. Studies around the world have shown that marijuana has considerable promise as a medicine.

Craker says he spoke late last year at a hospital in New Hampshire where certain cannabinoids were shown to facilitate healing in brain-damaged mice. “And I thought, ‘If cannabinoids could do that, let’s put them in medicines!’ ” He sighs. “We can’t do the research.”

Another sigh. “I’m naive about a lot about things,” he says. “But it seems to me that we should be looking at cannabis. I mean, if it’s going to kill people, let’s know that and get rid of it. If it’s going to help people, let’s know that and expand on it. … But there’s just something wrong with the DEA.

I don’t know what else to say. … Somehow, marijuana’s got a bad name. And it’s tough to let go of.”

Craker looks over some of the plants used in studies in the agriculture department’s greenhouse at UMass.

Photographer: Jonathan Schoonover for Bloomberg Businessweek

Back

in 1990, Ethan Russo was a practicing neurologist who’d grown

frustrated with his pharmaceutical options. “It occurred to me I was

giving increasingly toxic drugs to my patients with less and less

benefit,” says Russo, now one of the world’s leading experts and advocates

for research in marijuana medicine. “It caused me to go back to a

childhood interest in medicinal plants and see if there were

alternatives.”

Obviously, he’d need to use NIDA-supplied marijuana. You can’t do research acceptable to the FDA with marijuana grown illegally, as is all marijuana not grown at Ole Miss.

NIDA twice rejected his applications to use its pot, but then the FDA assumed oversight of what it calls “investigational new drug” applications, and Russo got his approval. In the eyes of the FDA, his study was promising enough to warrant a clinical trial. “With any other drug, I would have been able to begin work on the trial the next day,” he says. But the use of cannabis, and only cannabis, required a second “public health service review,” according to a rule instituted in 1998 to, ostensibly, facilitate more research. In reality, it did the opposite. NIDA denied Russo access to its cannabis. “Despite the fact that the FDA had approved it,” he says.

Around the world, cannabis research was a growing field. Russo began to write and publish on the subject, and in 1998 he was recruited as a consultant by a British startup, GW Pharmaceuticals Plc, founded by two physicians who’d been granted a license to cultivate cannabis by the U.K. Home Office, which oversees, among other things, security and drug policy.

It’s just that in the U.S., the only federally legal pot is from Ole Miss.) Sativex is now available in every country in which trials were conducted except the U.S., where GW expects approval soon.

“Basically, I had begun working for a foreign company because of the impossibility of doing clinical work with cannabis in the United States,” Russo says. “And here we had a situation where a medicine, made from cannabis, that was manufactured in England, was able to be imported and tested. It was legally impossible to do the same thing based in the U.S.” GW has a market value of more than $2 billion and a robust drug development pipeline.

Doblin’s ultimate goal isn’t to compete with GW Pharmaceuticals. Should the NIDA monopoly ever end, he says, a number of companies will surely want to grow marijuana “to make extracts in nonsmoking delivery systems that can be patented”—that is, pharmaceuticals. This is a good thing, in his estimation. “But MAPS is focused on developing a low-cost generic plant in bud form,” he says.

In other words, he wants specific varieties of marijuana, not derivatives thereof, to be FDA-approved.

Many people expect the Republican-controlled Congress to follow its recent tax overhaul by looking for ways to slash costs in Medicaid and Medicare. Legitimate research into the medicinal properties of marijuana could help. Studies show that opioid use drops significantly in states where marijuana has been legalized; this suggests people are consuming the plant for pain, something they could be doing more effectively if physicians and the FDA controlled chemical makeup and potency. A study published in July 2016 in Health Affairs showed that the use of prescription drugs for which marijuana could serve as a clinical alternative “fell significantly,” saving hundreds of millions of dollars among users of Medicare Part D.

“The marijuana plant in bud form, if we can get it available by the FDA, is going to be incredibly cheap,” Doblin says. His Israeli partners, Better by Cann Pharmaceuticals, can produce organic, high-potency trimmed marijuana for roughly 65¢ a gram, or $18 or so per ounce. “When you’re talking about kicking people off of health insurance and reducing Medicare and Medicaid costs, we better find a way to provide medical relief to people at a low cost,” he says.

Russo agrees. He now lives in Washington state consulting for several biotech startups working on cannabis projects. “Let’s face facts: This is a very technologically advanced nation with a great deal of talent. There is no way, shape, or form that the dangers of cannabis warrant this kind of control,” he says. “There are issues. There are side effects. Anyone who tells you differently is simply inaccurate. However, the kinds of problems related to cannabis administration are totally controllable. And it is a much safer drug than many, if not most, pharmaceuticals that are currently being approved.”

He’d just returned from an industry conference in Medellín, Colombia. “I think that there’s a greater chance of significant clinical cannabis research coming out of Colombia in the coming years than there is in the U.S.,” Russo says. “Why would people allow this loss of business in a situation where, clearly, Americans could be preeminent?”

Among

those who’ve advised Craker is Tony Coulson, a former DEA agent who

retired in 2010 and works as a consultant for companies developing

drugs. Coulson was vehemently antimarijuana until his son, a combat

soldier, came home from the Middle East with post-traumatic stress

disorder and needed help. “For years I was of the belief that the

science doesn’t say that this is medicine,” he says.

“But when you get

into this curious history, you find the science doesn’t show it

primarily because we’re standing in the way. The NIDA monopoly prevents

anyone from getting into further studies.”

“I guess I take a nationalist approach here,” says Rick Kimball, a former investment banker who’s raising money for a marijuana-related private equity fund and is a trustee for marijuana policy at the Brookings Institution. “We have a huge opportunity in the U.S.,” he says, “and we ought to get our act together. I’m worried that we’re ceding this whole market to the Israelis.”

From left: Craker in his lab; inspecting samples of grass being grown in a cooler.

Photographer: Jonathan Schoonover for Bloomberg Businessweek

At foreign labs, and even at state-licensed operations in Colorado and Washington, plant scientists are growing genetically modified varieties that optimize for certain properties. The majority of their work is focused on increasing potency for recreational use—getting people high—but these companies are learning how to cultivate and engineer plants using increasingly sophisticated methods.

Meanwhile, Mahmoud ElSohly, director of the Marijuana Project at Ole Miss, is growing limited varieties, outdoors, while trying to keep undergrads from breaching his security. (At one point, students were caught using fly rods to cast over the fence and steal buds.) It took ElSohly three years to get DEA permission to grow a strain high in CBD, a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid thought to have many healthful properties. The key ingredient in GW Pharmaceutical’s epilepsy drug, it may have promise as an anti-inflammatory and antipsychotic.

“I am the most restricted person in this country when it comes to production of cannabis and different varieties,” ElSohly says. “In Colorado and Washington or any other state where people don’t have to get any approval from anybody, they just do it. They have the freedom to experiment. I don’t have that freedom. My hands are tied. It’s ridiculous.”

It appears that none of the 25 applications to grow marijuana for purposes of medical research have gone anywhere. (The DEA won’t comment on this or release the names of the applicants.) Craker has yet to get a single call or email about his methods or motivations. No agent has come to inspect his facility or ask questions about security.

He marvels at the power of bureaucratic inertia: “The federal government can be so stubborn. To me they’ve closed their minds.” Craker can’t grow marijuana, but he does lecture about it in his plant medicine classes. “I go through the scenario of what we’ve tried to do,” he says. Ultimately, he says, some of those students may have to do the work he’s been wanting to do for 20 years.

“My generation has passed, and we haven’t made it. But it’s going to happen. I just can’t believe it’s going to be forever.”

No comments:

Post a Comment