Bills to loosen marijuana laws are gaining traction in both parties

Legalizing marijuana is no longer a single-party issue.

Elizabeth Warren and other Democratic presidential contenders have found

common ground with Republicans like Cory Gardner. (Sarah Silbiger/CQ

Roll Call)

An unlikely coalition

of lawmakers is plotting how to revise the nation’s marijuana laws

during the 116th Congress — a mission that’s become much more viable in

recent years as public support for legalizing cannabis shoots up and

members introduce bills in higher numbers than ever before.

That legislation languished at the bottom of the hopper during the last Congress as GOP leaders remained steadfast in their opposition. But now advocates are optimistic that Democratic control of the House and mounting pressure to clean up the disparity between state and federal laws could propel some incremental changes through the Republican-controlled Senate — even if it will be a challenge.

At the top of the bipartisan wish list are bills to fix the banking, tax and legal gray areas that have emerged as more and more states set up marijuana dispensaries in open defiance of federal law.

Watch: Wait, there’s a Cannabis Caucus? Pot proponents on the Hill say it’s high time for serious policy debate

That legislation languished at the bottom of the hopper during the last Congress as GOP leaders remained steadfast in their opposition. But now advocates are optimistic that Democratic control of the House and mounting pressure to clean up the disparity between state and federal laws could propel some incremental changes through the Republican-controlled Senate — even if it will be a challenge.

At the top of the bipartisan wish list are bills to fix the banking, tax and legal gray areas that have emerged as more and more states set up marijuana dispensaries in open defiance of federal law.

Watch: Wait, there’s a Cannabis Caucus? Pot proponents on the Hill say it’s high time for serious policy debate

Veterans in states that have legalized medical marijuana also can’t get a prescription from their VA doctors under current law.

“The federal government can’t just stick its head in the sand and pretend this is going to go away,” said Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner, a Republican up for re-election in 2020 in an increasingly blue state with legal medical and recreational marijuana.

At a time when Washington politics is often defined as two sides entrenched in opposing views, marijuana has become one of the few issues where some politicians have actually changed their opinions.

The shift is driven by Americans’ growing acceptance of medical and recreational use and the old maxim that all politics is local.

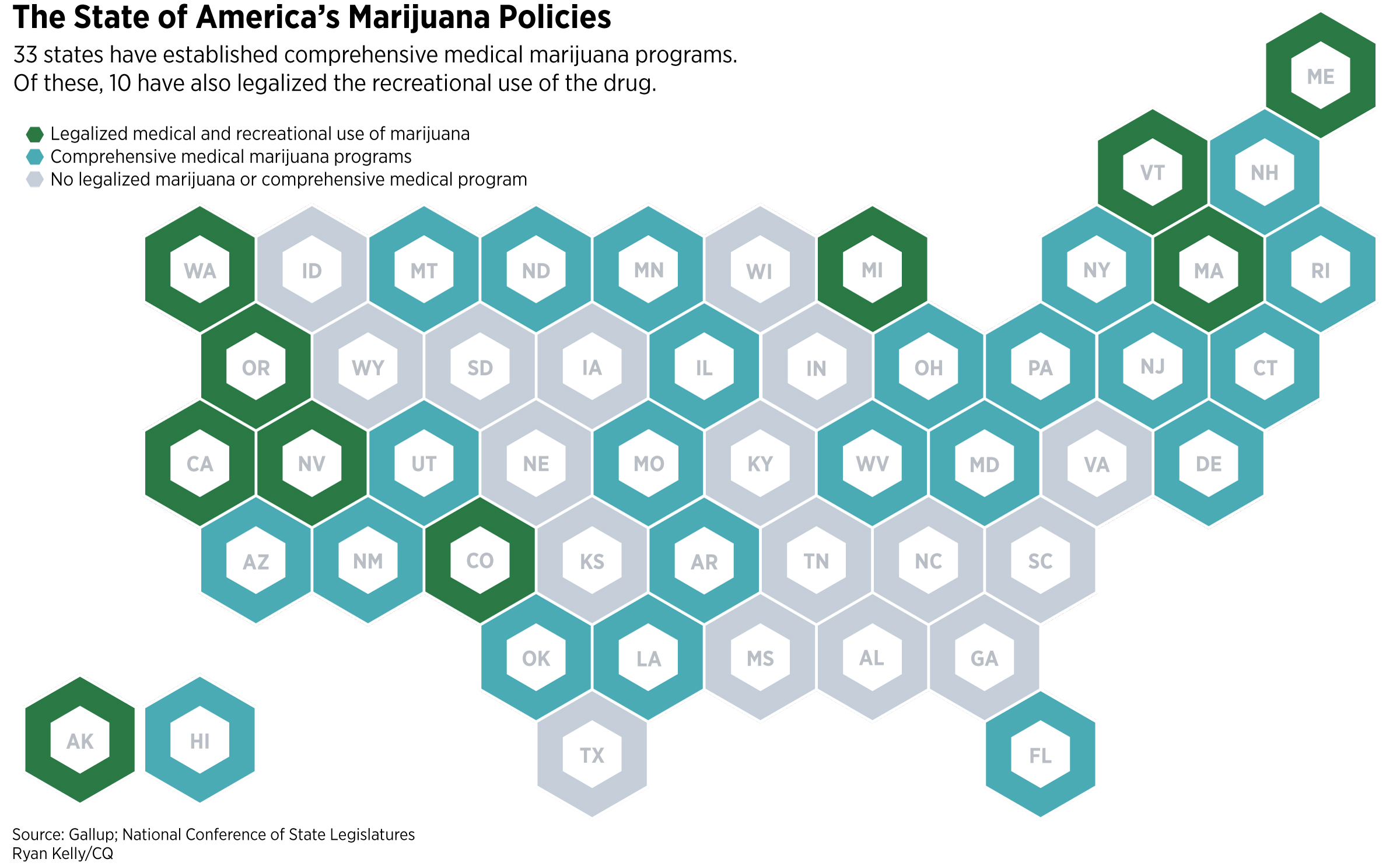

So far 33 states have approved comprehensive medical marijuana programs, with 10 of them opting to allow recreational use as well — a decision that has poured millions of dollars into state coffers and galvanized many GOP members to tell the federal government “hands off.”

New attitudes

John Hudak, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, said two factors are driving a somewhat rapid change in public opinion. The first is “generational replacement,” which is when older voters who are overwhelmingly opposed to pot policy changes are replaced by younger voters who predominantly favor legalization. The second is that the majority of the concerns raised by marijuana opponents have fallen flat.“A lot of Americans look around at the country — at states with medical and adult use — and they see the sky hasn’t fallen, the doomsday predictions of naysayers have not really come to fruition,” Hudak said.

Momentum behind congressional action has been building for more than two decades, since California first voted to legalize medical marijuana in 1996, with pressure increasing sharply when Washington and Colorado voted to legalize recreational use in 2012.

Within a year of those decisions, nationwide support for legalization jumped from 48 to 58 percent — the first time a majority of Americans supported outright legalization since Gallup began polling on the issue in the 1960s. The number has been climbing steadily ever since and promises to be even higher by election time next year.

Ballot measures to loosen restrictions on marijuana are likely to show up in key swing states during the next election, driving Democratic turnout and putting pressure on Republicans to take action.

That could lead to some difficult decisions for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, tasked with defending the GOP Senate during what promises to be an interesting and possibly absurd campaign cycle.

“There’s a broader calculus here for Sen. McConnell,” said Hudak. “If he is able to bring forward a piece of legislation that would help Cory Gardner or Susan Collins get re-elected, surely there’s an interest in doing that. The flip side of that is Sen. McConnell doesn’t want to put his other members in a difficult position.”

It’s unclear whether action on marijuana legislation in the Senate would, in fact, help Collins, since a ballot initiative for recreational use in Maine passed by a mere 3,995 votes in 2016. And, unlike some of her colleagues, she’s not particularly vocal on the topic.

Gardner, however, has become a key Republican voice for change in the Senate. Like many Americans, his way of thinking evolved after seeing how his state set up and addressed concerns surrounding recreational marijuana use.

Nationally, support for legalizing marijuana has increased drastically since the new millennium began, more than doubling from 31 percent in 2000 to 66 percent in 2018, according to Gallup polling. Democrats have been on the bandwagon longer and are generally more supportive, with 75 percent of those polled currently in favor of legalization. But Republicans have been coming around to the idea as well, with 53 percent of those polled in October supporting legalization — an increase of 11 percentage points from just two years earlier, when 42 percent supported legalization.

The sharp and fast rise in states with some type of legal marijuana drove the creation of the Congressional Cannabis Caucus two years ago.

The group has reorganized for this Congress, adding left-leaning Barbara Lee of California and moderate Republican David Joyce of Ohio to its leadership team of Earl Blumenauer, an Oregon Democrat, and Alaska’s Young.

The fact that they are a somewhat odd collection of lawmakers hasn’t escaped the group’s attention, but they don’t expect it will deter them from working together to get common-sense bills onto the House floor — and possibly through the Senate.

“Don Young is not a progressive African-American woman, but I am. And we have Don Young and Barbara Lee working together on something,” Lee said. “It’s all about working for the people — and when 66 percent of the public say they want something, I think it’s time we do something.”

Justin Strekal, political director for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, believes some legislation can advance during the next two years.

“I do think that there is a real chance that we’re going to be able to make progress; at least in restricting federal enforcement, particularly in the states that have moved forward in clear defiance of federal law,” Strekal said. “As of right now, we are in this very uneasy détente.”

Singular success

Medical marijuana dispensaries following state laws have been somewhat protected since December 2014, when appropriators added a paragraph to the fiscal 2015 omnibus that barred the Department of Justice from interfering with the “use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of medical marijuana” in 32 states and the District of Columbia. That list has grown substantially during the past four years to include 46 states as well as the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam and Puerto Rico.But protecting medical marijuana businesses operating within their respective state laws falls short of the type of sweeping overhaul advocates hope to accomplish.

Lee, for example, would like to advance legislation originally introduced last year that would remove marijuana as a Schedule I substance, essentially legalizing it; expunge the records of anyone convicted in a federal court of marijuana possession; and establish a fund that would assist communities most affected by the “war on drugs” with job training and similar programs.

The legislation received no Republican co-sponsors, but a virtual Who’s Who of 2020 Democratic presidential candidates signed on in the Senate, including Cory Booker of New Jersey, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Kamala Harris of California, Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

Though the bill, just reintroduced by a similar coalition, has long odds of being taken up in the GOP-controlled Senate, Lee hopes to convey to her fellow lawmakers that protecting states or loosening federal restrictions around marijuana is no longer about whether members actually support its use.

“It has nothing to do with whether you agree or disagree with the whole issue of marijuana; it’s about the laws that have been changed,” Lee said. “We’ve got to make sure they are regulated and they are complied with and that they work.”

The bill that has the best chance of passing both chambers and actually being signed into law by President Donald Trump this Congress was originally introduced last June by Gardner, Warren, Blumenauer, Joyce and several of their colleagues.

It would amend the Controlled Substances Act so a dispensary in line with its state’s laws would no longer be violating federal laws.

That would likely give banks enough assurance to openly do business with marijuana companies without worrying about being complicit in money laundering under federal law. Dispensaries could also begin deducting business expenses on their taxes. The legislation would, however, keep marijuana as a Schedule I substance.

Gardner said the bill’s “simple federalism approach” has the support of enough senators to pass the Republican-controlled chamber and that Trump has said he supports the efforts. But he admits he’ll face a challenge getting Judiciary Chairman Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican, to bring the bill up for a hearing — let alone a vote — and an even bigger challenge is getting McConnell to bring it to the floor.

Gardner said his goal is to convince Republicans that just ignoring the conflict between state and federal law is no longer an option.

“States are not going to go back,” Gardner said. “They are not going to put the ketchup back in the bottle.”

Graham, however, doesn’t appear interested in having the Judiciary Committee debate Gardner’s bill or any other marijuana legislation.

“We’re trying to sit down and think of a legislative agenda where we can find common ground, and I’m not so sure that one brings us together,” Graham said.

A more likely avenue to success for cannabis policy may be in must-pass spending bills.

A key legal reason medical marijuana dispensaries are insulated from federal law enforcement is that appropriators have added a provision to the last five Department of Justice spending bills preventing it from interfering with medical dispensaries.

So far, that’s the only provision that has made it into a final spending bill.

Appropriators have proposed additional amendments, including allowing the Department of Veterans Affairs to prescribe medical marijuana in states that have legalized it and encouraging the Drug Enforcement Administration to actually process applications for companies that want to grow marijuana for research purposes. But neither has made it into law.

Senate Republican Policy Committee Chairman Roy Blunt of Missouri said he expects spending bills will continue to be the place where marijuana policy is debated for the foreseeable future.

“I’d be surprised if [McConnell] would want to spend a lot of time on that, particularly with the issues that involve the difference in the way the federal government looks at this issue and the way the state governments are beginning to look at this issue,” said Blunt, who oversees the massive Labor-HHS-Education spending bill for Senate Republicans. “We are likely to deal with it somewhere, but I think that would be more likely in the appropriations bills.”

High hopes

Despite the obstacles ahead, the Cannabis Caucus remains optimistic that Congress will take marijuana policy more seriously than it has during previous sessions. And it appears a majority of Americans are on their side.Support for legalization has been steadily increasing in both political parties since California became the first state to legalize medical marijuana more than 22 years ago.

At the time, the odds of cannabis policy being seriously discussed within the halls of Congress were dismally low. And national debate about the issue was virtually nonexistent, with then-President Bill Clinton opposed to loosening any restrictions on the plant despite having smoked weed (without inhaling) while at the University of Oxford.

During the following two decades, familiarity with and knowledge about the impacts of marijuana shifted as the number of states with legal marijuana programs swelled.

In many cases, as the number of Americans with access to legal marijuana steadily increased, so did the percentage of voters supporting it.

In 2000, near the end of Clinton’s presidency, just 31 percent of those polled by Gallup favored legalization. By 2010, when Barack Obama — who openly wrote about smoking marijuana during his youth — was president, 16 states had approved medical marijuana, and support for outright legalization was up to 46 percent.

The turning point for legalization came in 2012 when Washington and Colorado legalized recreational use. They were followed by Alaska, Oregon, Massachusetts, Maine, Nevada, California, Vermont and Michigan. During that time, support for legalization jumped from 48 percent in 2012 to 66 percent in 2018, according to Gallup.

Feds vs. states

The increase in states with legal marijuana led to some confusion about the types of cases federal prosecutors should pursue. Deputy Attorney General James Cole sought to clarify that in August 2013 when he released a memo outlining just eight reasons the federal government would seek to enforce federal law in states with legal cannabis.But that guidance was rescinded in January 2018 by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, a vocal opponent of legal cannabis who once said “good people don’t smoke marijuana.”

The new attorney general, William Barr, doesn’t plan on contradicting the Cole memo in the way Sessions tried to, even if he believes there should be uniformity between federal law and state law on the issue.

“I think the current situation is untenable and really has to be addressed. It’s almost like a backdoor nullification of federal law,” Barr said in January during his confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

“I’m not going to go after companies that have relied on the Cole memorandum,” Barr continued.

“However, we should either have a federal law that prohibits marijuana everywhere, which I would support myself because I think it’s a mistake to back off on marijuana ... [or] if we want states to have their own laws, then let’s get there and let’s get there the right way.”

For now, addressing the disparity between state and federal laws doesn’t appear to be a high priority for GOP leaders; even if the “devil’s lettuce” has converted former House Speaker John A. Boehner, who announced last April that his “thinking on cannabis has evolved.” Among the changes he suggested is removing marijuana from the Controlled Substances Act’s Schedule I classification, which is intended for drugs with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

“I’m convinced descheduling the drug is needed so we can do research, help our veterans and reverse the opioid epidemic ravaging our communities,” he tweeted after joining the board of cannabis corporation Acreage Holdings.

Big business

But if an increasing number of prominent political voices, 66 percent of the voting public and the insistence of key lawmakers doesn’t offer the type of incentive congressional leaders need to bring policy bills to the floor just yet, the sheer size of the industry could.Marijuana sales were pegged at $8.5 billion in 2017 and are expected to reach $23 billion by 2022, according to BDS Analytics, which tracks the legal marijuana marketplace. In Colorado alone, there was $1.55 billion in sales during 2018, with $1.2 billion of that coming from recreational and $332 million from medical uses — more than double the $683.5 million in total sales during 2014.

States are also gaining millions of dollars in revenue annually from legal marijuana. In fiscal 2017, Washington state reported $319 million from taxes on the plant — nearly $130 million more than the prior fiscal year. Colorado collected $266 million from cannabis taxes during calendar year 2018, a steady increase from the $67 million it gained during 2014. During California’s first year of taxing recreational marijuana, the state brought in $345 million in revenue.

The industry has become far more than college students trying to grow weed in their dorm rooms and teenagers making jokes about “420” (the universal phrase for getting stoned).

While Blumenauer and Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden, a fellow Oregonian, did inject a little humor by introducing their respective policy bills as H.R. 420 and S. 420, marijuana is now a multibillion-dollar industry that pays millions into state coffers every year.

Marijuana’s illegal status is already part of the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, with candidates approaching the issue as an area for serious policy discussion and not something to be avoided.

And pot is no longer the taboo subject that Clinton once tried to dance around while running for president. Harris recently divulged that she smoked a joint in college.

“I have and I did inhale,” she said on morning radio show “The Breakfast Club,” while reiterating her support for legalization.

So even if the cannabis advocates can’t get sweeping changes to marijuana policy enacted this Congress, the outlook may be much different in two more years.

No comments:

Post a Comment