UNIVERSITY NEWS

Laboratory tests conducted at the University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute have shown that a modified form of medicinal cannabis can kill or inhibit cancer cells without impacting normal cells, revealing its potential as a treatment rather than simply a relief medication.

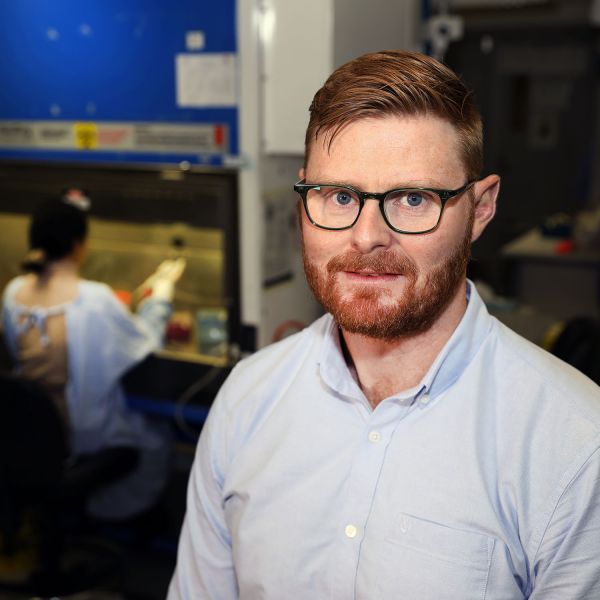

The significant outcome follows three years of investigations by cancer researcher Dr Matt Dun in collaboration with biotech company Australian Natural Therapeutics Group (ANTG), which produces a cannabis variety containing less than 1 per cent THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) – the psychoactive component commonly associated with marijuana. The plant, known as ‘Eve’, has high levels of the compound cannabidiol (CBD).

“ANTG wanted me to test it against cancer, so we initially used leukaemia cells and were really surprised by how sensitive they were,” Dr Dun says. “At the same time, the cannabis didn’t kill normal bone marrow cells, nor normal healthy neutrophils [white blood cells].

“We then realised there was a cancer-selective mechanism involved, and we’ve spent the past couple of years trying to find the answer.”

The Dun team has run comparisons between THC-containing cannabis, and cannabis lacking THC but with elevated levels of CBD. They found that, for both leukaemia and paediatric brainstem glioma, the CBD-enriched variety was more effective at killing cancer cells than THC varieties.

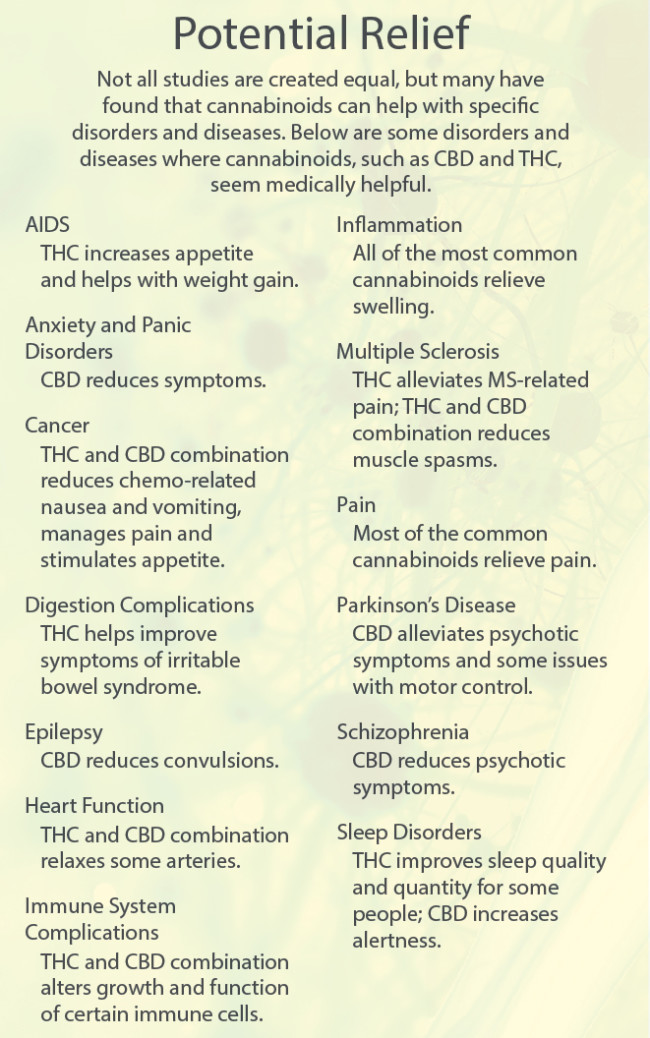

In a recent paper entitled “Can Hemp Help?”, released by international journal Cancers, Dr Dun and his team also undertook a literature review of over 150 academic papers that investigated the health benefits, side-effects, and possible anti-cancer benefits of both CBD and THC.

“There are trials around the world testing cannabis formulations containing THC as a cancer treatment, but if you’re on that therapy your quality of life is impacted,” Dr Dun says. “You can’t drive, for example, and clinicians are justifiably reluctant to prescribe a child something that could cause hallucinations or other side-effects.

“The CBD variety looks to have greater efficacy, low toxicity and fewer side-effects, which potentially makes it an ideal complementary therapy to combine with other anti-cancer compounds.”

The next phase for the study includes investigating what makes cancer cells sensitive and normal cells not, whether it is clinically relevant, and whether a variety of cancers respond.

“We need to understand the mechanism so we can find ways to add other drugs that amplify the effect, and week by week we’re getting more clues. It’s really exciting and important if we want to move this into a therapeutic,” Dr Dun adds, stressing that CBD-enriched cannabis isn’t yet ready for clinical use as an anti-cancer agent.

“Hopefully our work will help to lessen the stigma behind prescribing cannabis, particularly varieties that have minimal side-effects, especially if used in combination with current standard-of-care therapies and radiotherapy. Until then, though, people should continue to seek advice from their usual medical practitioner.”

The study was funded by ANTG and HMRI through the Sandi Rose Foundation.

“We are very pleased to see three years of collaboration with UON and HMRI deliver such exciting findings in the fight against cancer. ANTG remains committed to its patient-centric mission of understanding the massive therapeutic potential of medicinal cannabis," Matthew Cantelo, CEO, Australian Natural Therapeutics Group, said.

"We thank Matt Dun and the team for such encouraging insights into anti-cancer properties of our Australian grown CBD strain, Eve. We are looking forward to moving forward to the next stage of the study and continuing to develop effective, safe and consistent cannabis medicines for Australian patients.”

* Dr Matt Dun is from the University of Newcastle, researching in conjunction with the Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) Cancer Program. HMRI is a partnership between the University of Newcastle, Hunter New England Health and the community.